Researchers from the Bangor University, in Wales, unveiled how children and adults see social interactions differently in an article published in a high-impact journal this April. The results show how the brain makes sense of complex social behaviour, which could help us further understand and treat schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders.

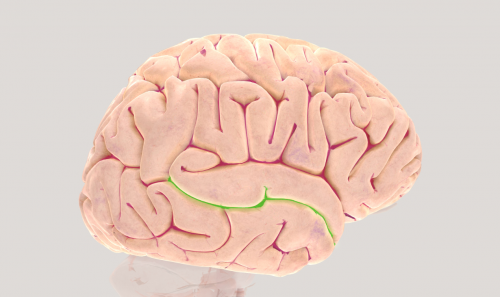

The team (which includes Jon, who is now working with us) performed a study with 29 adults and 31 children between 6 and 12 years old, focused on a brain area called superior temporal sulcus (STS), known to play an important role in social cognition such as facial recognition and body movement. The experiment was carried out using functional magnetic resonance imaging, allowing the visualization of the intensity of the response of STS when some visual stimuli were shown to the participants.

The results show significant differences in the response of the superior temporal sulcus (STS) between adults and children. Although there are differences in both hemispheres, they are bigger in the left hemisphere. “The distinction between the two hemispheres lead us to believe that the STS is still under development in children. Their ability to perceive social interactions is not completely matured yet”, clarifies Jon Walbrin, the researcher responsible for the study, now working at the University of Coimbra, in Portugal. The development of the STS seems to happen first in the right hemisphere and only in adults the STS response is strong in both sides of the brain. “Studying the maturity of areas closely related to the perception of social cues could be particularly useful to study the social cognition-related diseases such as schizophrenia or autism spectrum disorders, says the author.

The study was aimed at understanding how responsive the STS is to social interactions. To assess that, the participants visualized dot-pattern images while they were inside the MRI. One stimulus represented a social interaction between two human figures and in the other, the figures were not interacting. The selectivity of STS to social interactions was measured by the difference of the responses between the first and the second stimulus, that is, how much the STS responded specifically to social interactions.

A deeper analysis of the results showed significant differences even between the children. “We also showed that the selectivity of the STS in the right hemisphere was similar between older children (9-11 yo) and adults. The younger children, however, show much weaker interaction responses”, states Jon Walbrin.

The results in the left hemisphere suggest the STS’ selectivity increases with age, supporting the hypothesis of incomplete maturation in children. “The context of social interactions varies a lot from culture to culture. It makes sense that this ability to understand them is not completely innate but rather moulded by our experiences and by the context in which we live in”, continues. About the next steps, the researcher says it would be important to “replicate this study to all age groups and to include other brain areas we know could also have an important role in the perception of social interactions”, concludes.